Jennifer Allen

Assistant Professor

NYU Stern School of Business, Technology, Operations, and Statistics Department

About Me

I am an Assistant Professor at NYU Stern in the Technology, Operations, and Statistics Department, as well as a research affiliate of the Center for Social Media and Politics.

I’m a computational social scientist interested in digital persuasion, misinformation, and the wisdom of crowds. I received my PhD in Marketing from MIT Sloan School of Management advised by David Rand, and then completed a post-doc in the Computational Social Science Lab at the University of Pennsylvania. My research uses computational methods and real-world data to study how digital media contributes to societal problems, and how we can design scalable solutions.

Prior to my PhD, I worked as a software engineer at Meta on the News and Civic teams, and then as a research assistant at Microsoft Research with the Computational Social Science Group. Before that, I graduated from Yale in 2016 with a degree in Computer Science and Psychology. In my spare time, I enjoy pop culture trivia, yoga, and 5-star NYTimes recipes (wisdom of crowds!).

- Computational Social Science

- Digital persuasion

- Misinformation

- Crowdsourcing

-

PhD in Marketing, 2024

MIT Sloan School of Management

-

BA in Computer Science and Psychology, 2016

Yale

Featured Publications

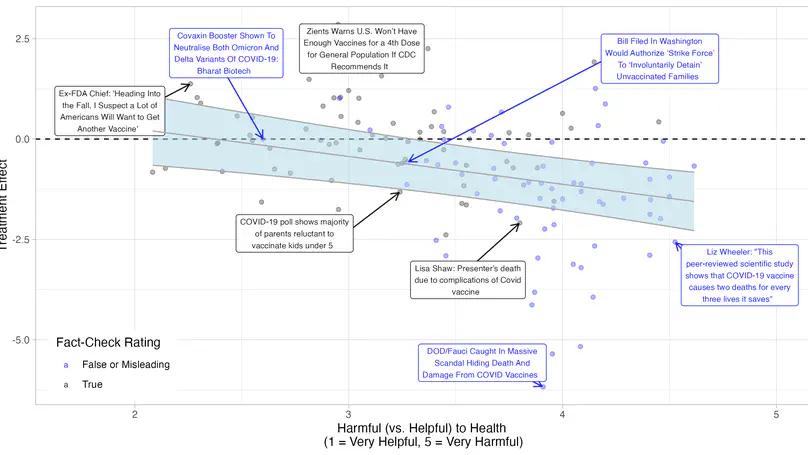

Researchers and public health officials have attributed low uptake of the COVID-19 vaccine in the US to social media misinformation. To evaluate this claim, we introduce a framework combining lab experiments, crowdsourcing, and machine learning to estimate the causal effect of 13,206 vaccine-related URLs shared on Facebook on US vaccination intentions. Our model predicts this content reduced intentions by-2.3 percentage points (95% QI:-3.5,-1.0) per US Facebook user. Strikingly, we estimate the impact of misinformation was 50X less than that of content not flagged by fact-checkers that nonetheless expressed vaccine skepticism. Although misinformation was significantly more harmful when viewed, its exposure on Facebook was limited. In contrast, mainstream stories highlighting rare vaccine deaths both increased vaccine hesitancy and were among Facebook’s most-viewed stories. Our work suggests that curbing misinformation benefits public health, but highlights the need to scrutinize factually correct but potentially misleading content.

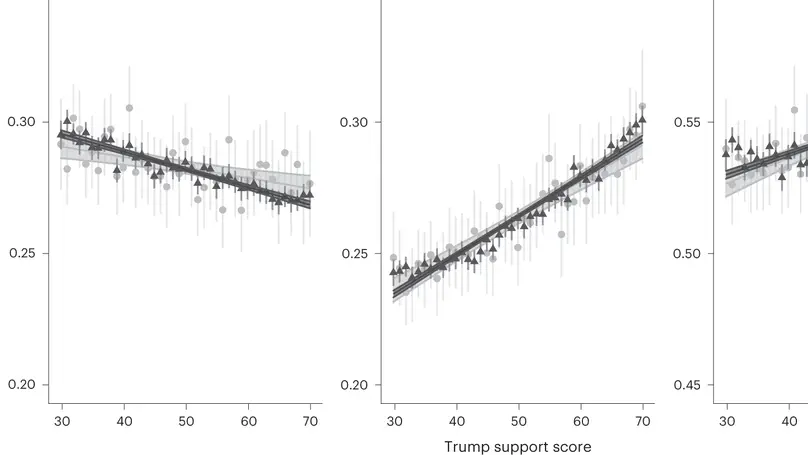

We present the results of a large, US$8.9 million campaign-wide field experiment, conducted among 2 million moderate- and low-information persuadable voters in five battleground states during the 2020 US presidential election. Treatment group participants were exposed to an 8-month-long advertising programme delivered via social media, designed to persuade people to vote against Donald Trump and for Joe Biden. We found no evidence that the programme increased or decreased turnout on average. We found evidence of differential turnout effects by modelled level of Trump support: the campaign increased voting among Biden leaners by 0.4 percentage points (s.e.=0.2pp) and decreased voting among Trump leaners by 0.3 percentage points (s.e.=0.3pp) for a difference in conditional average treatment effects of 0.7 points (t(1,035,571)=−2.09; P=0.036; points; 95% confidence interval=−0.014 to 0). An important but exploratory finding is that the strongest differential effects appear in early voting data, which may inform future work on early campaigning in a post-COVID electoral environment. Our results indicate that differential mobilization effects of even large digital advertising campaigns in presidential elections are likely to be modest.

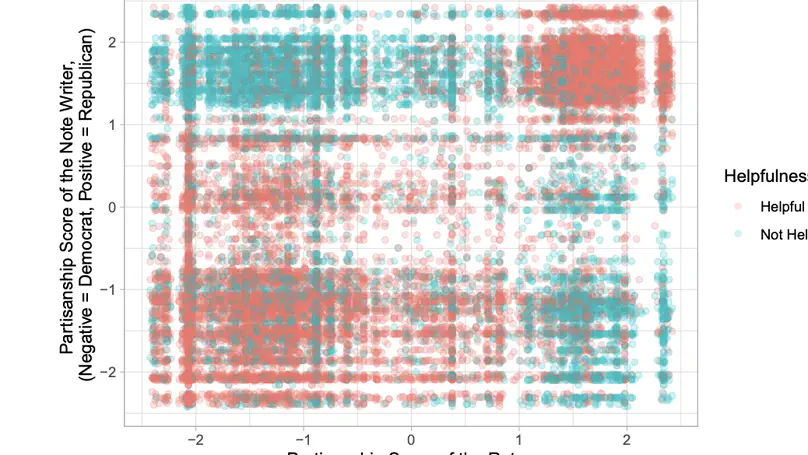

There is a great deal of interest in the role that partisanship, and cross-party animosity in particular, plays in interactions on social media. Most prior research, however, must infer users’ judgments of others’ posts from engagement data. Here, we leverage data from Birdwatch, Twitter’s crowdsourced fact-checking pilot program, to directly measure judgments of whether other users’ tweets are misleading, and whether other users’ free-text evaluations of third-party tweets are helpful. For both sets of judgments, we find that contextual features – in particular, the partisanship of the users – are far more predictive of judgments than the content of the tweets and evaluations themselves. Specifically, users are more likely to write negative evaluations of tweets from counter-partisans; and are more likely to rate evaluations from counter-partisans as unhelpful. Our findings provide clear evidence that Birdwatch users preferentially challenge content from those with whom they disagree politically. While not necessarily indicating that Birdwatch is ineffective for identifying misleading content, these results demonstrate the important role that partisanship can play in content evaluation. Platform designers must consider the ramifications of partisanship when implementing crowdsourcing programs.

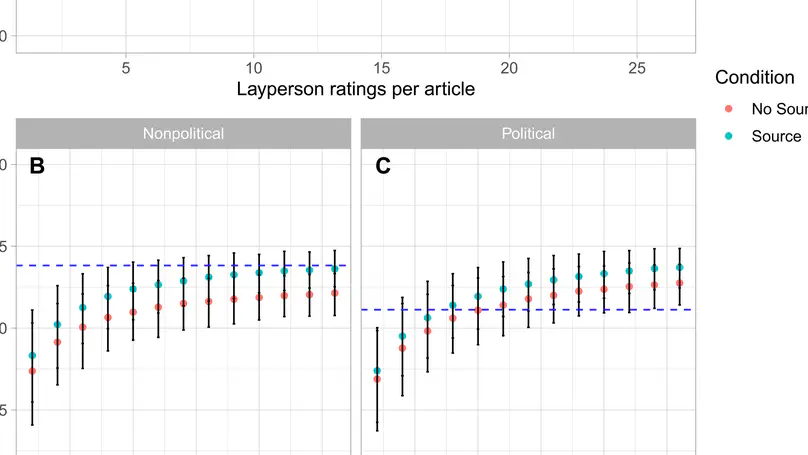

Professional fact-checking, a prominent approach to combating misinformation, does not scale easily. Furthermore, some distrust fact-checkers because of alleged liberal bias. We explore a solution to these problems: using politically balanced groups of laypeople to identify misinformation at scale. Examining 207 news articles flagged for fact-checking by Facebook algorithms, we compare accuracy ratings of three professional fact-checkers who researched each article to those of 1128 Americans from Amazon Mechanical Turk who rated each article’s headline and lede. The average ratings of small, politically balanced crowds of laypeople (i) correlate with the average fact-checker ratings as well as the fact-checkers’ ratings correlate with each other and (ii) predict whether the majority of fact-checkers rated a headline as “true” with high accuracy. Furthermore, cognitive reflection, political knowledge, and Democratic Party preference are positively related to agreement with fact-checkers, and identifying each headline’s publisher leads to a small increase in agreement with fact-checkers.

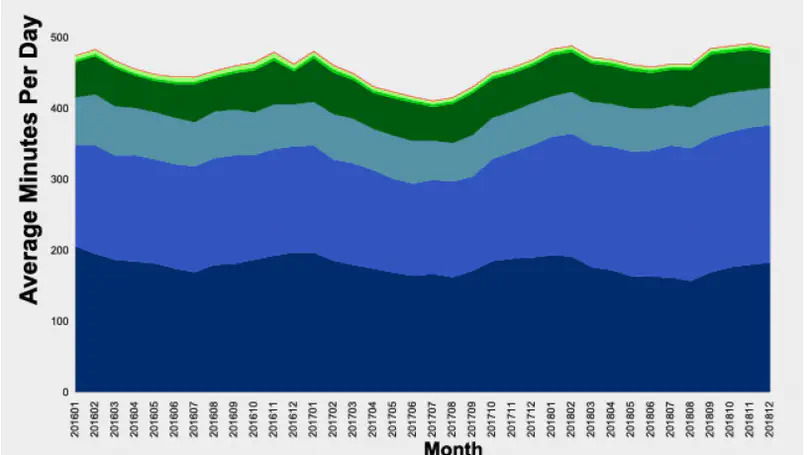

“Fake news,” broadly defined as false or misleading information masquerading as legitimate news, is frequently asserted to be pervasive online with serious consequences for democracy. Using a unique multimode dataset that comprises a nationally representative sample of mobile, desktop, and television consumption, we refute this conventional wisdom on three levels. First, news consumption of any sort is heavily outweighed by other forms of media consumption, comprising at most 14.2% of Americans’ daily media diets. Second, to the extent that Americans do consume news, it is overwhelmingly from television, which accounts for roughly five times as much as news consumption as online. Third, fake news comprises only 0.15% of Americans’ daily media diet. Our results suggest that the origins of public misinformedness and polarization are more likely to lie in the content of ordinary news or the avoidance of news altogether as they are in overt fakery.